Knuttel Retrospective

“I do not explain my work, rather my work explains me.”

Graham Knuttel, Dublin 2001

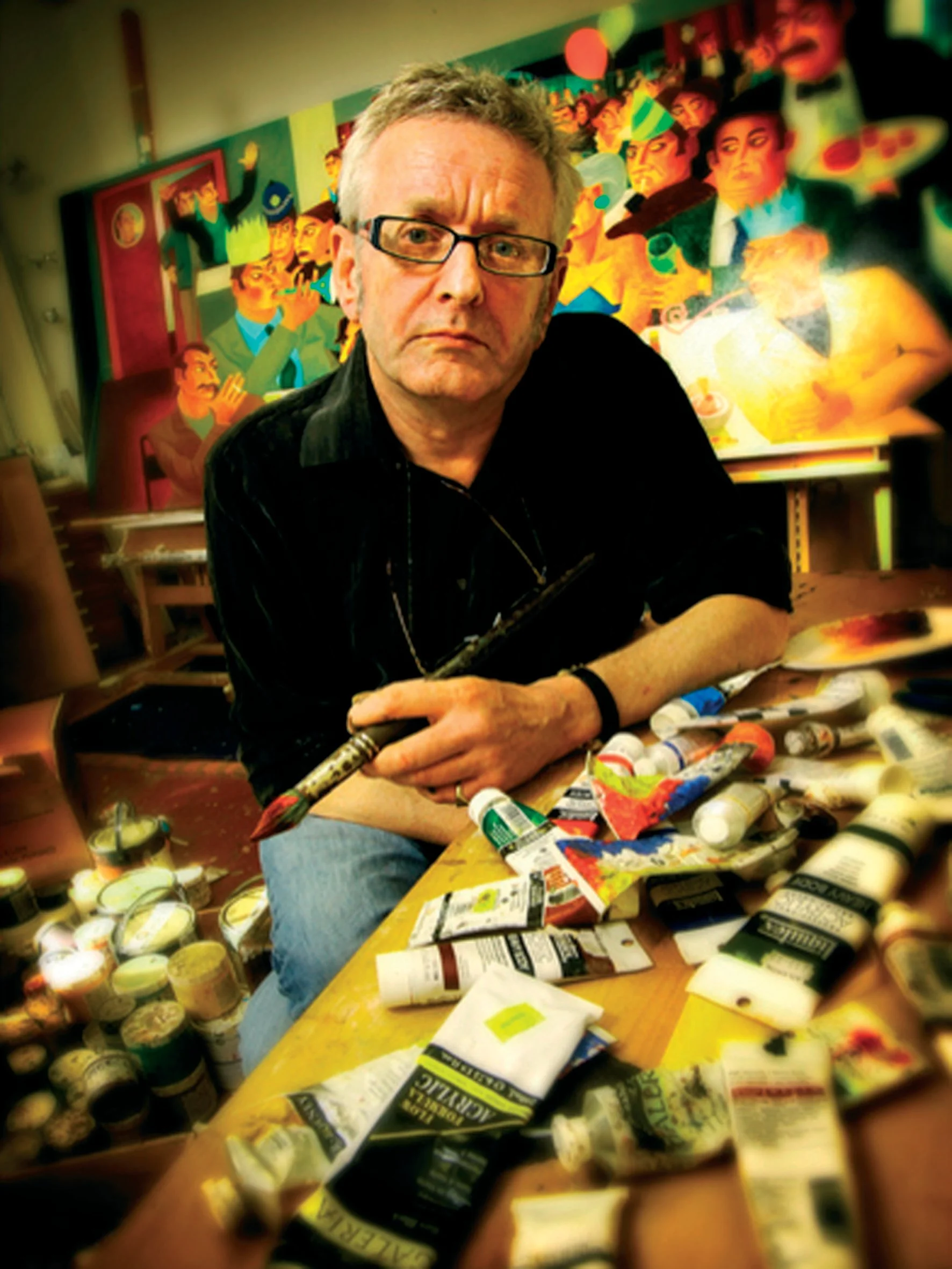

As colourful in life as in his art

Graham Knuttel was one of Ireland’s most distinctive and provocative artists, capturing the contradictions of modern life through his vivid, stylised works. His bold use of colour and sharp, angular figures portray shady characters, gangsters, and sultry women in a way that exposed the undercurrents of greed and power beneath the surface. Known internationally, Knuttel’s work attracted collectors such as Sylvester Stallone and Robert De Niro, cementing his place as a unique observer of contemporary society.

Born in Dublin in 1954 to an English mother and German father, his unconventional spirit set him apart at an early age. He spent his youth sketching the Dublin coastline and developing his talent, which led him to Dún Laoghaire College of Art and Design in 1972.

Though he initially focused on sculpture, his move into painting allowed him to craft the dynamic, narrative-driven style that would make him famous. Knuttel’s works were as much about storytelling as they were about form, with recurring themes of tension, desire, and corruption woven throughout his works. His ability to layer meaning and intrigue into every piece captivated audiences.

Photo courtesy of David Conaghy, Irish Independent

Graham's artistic journey was shaped by his ability to blend dark subject matter with vibrant, often jarring colours. His signature style, featuring angular figures and exaggerated expressions, conveyed a sense of tension and intrigue. His works didn’t just depict people but told stories, often hinting at the hidden desires, fears, and power dynamics of his subjects. His paintings of sharp-suited men, accompanied by seductive women or solitary figures, were not just portraits but commentaries on greed, corruption, and the undercurrents of human behavior.

In addition to his paintings, Knuttel became a prominent figure in Irish culture through his commercial collaborations. He designed stamps for An Post to mark the 2008 Beijing Olympics and created a chess set with Viscount Linley. While Projects like these allowed his work to reach a broader audience, they were never overshadowed by his more personal, introspective pieces. Even as his art became widely recognized, Knuttel maintained that his best work came from his obsessive need to depict the truths he saw in life - often blurring the line between his personal experiences and his art.

Knuttel’s personal life was as colourful as his canvases. His relationships with artist Anna McCleod and artist Rachel Strong and later his marriage to Ruth Mathers, who donated a kidney to him in 2022, often mirrored the passion and intensity found in his art. Throughout his career, Knuttel remained an astute chronicler of Irish society, capturing the glamour and danger of a country in transition.

Following his death, President Michael D. Higgins and Minister Catherine Martin acknowledged his immense contribution to the Irish art world, ensuring that his vibrant and thought-provoking legacy will endure for years to come.

“Throughout his life he made such a valuable contribution to Ireland’s artistic community.”

President of Ireland Michael D. Higgins

Graham Knuttel on his life and art

I was born in Dublin, in March 1954. My parents came to Ireland in 1947 from Bedford in England where my father had served with the R.A.F. My father, Adolf Knuttel, was a stone quarry owner in Dresden. Adolf and my grandmother came to England after the First World War.

My father was a strange eccentric man but had nothing on my grandmother. I met her only once when I was four or five but the memory will never leave me. She was very tall and thin with a hook-like nose not dissimilar to my own. Her cheeks were hollow, whitened with powder and highlighted with rouge. She was dressed all in black, except for a white lace frill at her neck. The sight of her beside my father’s huge dark wardrobe sent me into a state of total hysteria. There being no one else in the room, she tried to lock me in the wardrobe. I can still hear her cackling and feel her long white claws at the back of my neck.

I often look at my drawings of birds with which I have had a long obsession and wonder. I am glad that I managed to find some sort of humour in what I firmly believe was a very close call. I think she might easily have strangled me and possibly eaten me had not my cries been heard. She was returned that same day to Margate where she lived in a guest house surrounded by her collection of stuffed animals until her death in 1962.

In my last year of study, some new tutors arrived, fresh from post-graduate studies in America, and proved to be a dangerous lot altogether. They were rabid abstract expressionists to whom artists such as Barnet Newman assumed God-like status. My difficulty then was that I was isolated as a figurative painter and should I decline to imitate a transatlantic culture, I would certainly be doomed to failure. I found it pragmatic therefore to stop painting temporarily and adjourn to the sculpture department for my final year.

My tutor there was an elderly sculptor who had seen trends come and go over the years and who emphasised to me the qualities of the older painters Cezanne, Goya, Rembrandt. From his lifetime of carving wood and stone he was able to tell me something of the way that light reveals form and how paint can break the light into colours. It was a valuable year for me.

In 1976, I received my diploma for my exhibition of sinister moving wood constructions - a wooden bird, a portcullis, a shield, wooden machines reminiscent of medieval times - just as solidly built as my father's wardrobe. I developed a love for sculpture at this time and for some years worked hard in carving and construction. However, through drawing and using colour in my sculpture, I gradually found myself returning to painting. Nowadays I work as both a painter and a sculptor. For a young artist, the initial years are extremely tough and hazardous.

The bohemian life can be often dangerous too. My observations of humanity led me down some very dark alleyways indeed during my wilderness years, and like my grandfather I am also prone to shout in my sleep at my memories. At the beginning of 1987 I realised that I must mend my ways. I had a serious drink problem and 10 years of my work was now in the hands of irate publicans and landlords. I changed from being an alcoholic to a workaholic overnight with sensational results. Nowadays painting is an obsession for me. I have a strict discipline and I work from first light every morning until darkness, and beyond.

As I work, I use as source matter my experiences as a younger man. I like to paint the human predicament as I have seen it. My figures appear in an urban landscape of which I am part. I try to use colour and form to express the emotion of my figures. I have developed this to include portraiture which I find exhilarating. I prefer a nightmare world full of shadows where danger and savagery is always close to hand.

My own doubts and fears and hopes are expressed on the faces that appear in the bars and backrooms in my work. Mr. Punch is my alter ego. He reflects my moods. We fight the same battles from the same cupboards.

I return in my work constantly to still-life as a source of inspiration. Its potential for simplicity and invention and its deep roots in tradition bring me back to my student studies of Cezanne and Picasso.

I try not to concern myself overly with intellectual reasoning or planning in my work. As a hard- working painter, my concerns are mainly technical, practical, and immediate. My concern is to paint the picture first and think about it afterwards. That way I can progress in a proper manner. Above all I try to speak with my own voice and see with my own eyes.

My mother’s family were more normal. Many of my summer holidays were spent in their house in Northampton, then a small market town. My grandfather had been shell-shocked in Flanders during the First World War but the only manifestations of this that I could discern were a tendency to shout in his sleep all night and to cross roads as if he were in a trench, holding his hat, knees bent, gripping the wall firmly on the other side. He would take me to see my Uncle Freddie who was a municipal painter. Part of his brief was to maintain the various coats of arms and paint the war memorials throughout the town. We would sit in the sun for hours watching him paint his bright rich reds and blues, and his fine and important gold leaf highlights.

We went to England two or three times a year and I remember the atmosphere of that journey very well. We took The Princess Maud, a steamship notorious for its creaking and rolling, packed as it was in those days with emigrant faces. We made the journey at night with a three hour wait at dawn in Crewe Station for a connection. Under the grime and soot, it was a magnificent building with its ornate brickwork and cast and wrought iron.

In many ways the scenes were reminiscent of the air raid drawings of Henry Moore. Today when I draw people, I draw in caricature railway porters I have seen asleep on mail bags, weary worried men and women busy and intent on that awful survival.

My school days were not those of a model student, in fact, few of them were spent at school at all. With my schoolbag safely hidden in a neighbour's hedge, many mornings and afternoons were spent sampling the café society and pubs of Dublin and exploring the rocky coastline of Dublin Bay. As my interest on formal education waned, my absorption in drawing and painting grew. When I was eighteen, I started at art school. My years of training had given me an insight into the possibilities of bohemian life and art school suited me very well. I had always had interest in figurative work, in the portrayal of the human condition, and from an early age I was familiar with the work of Van Gogh, Cezanne and Picasso. In art school I was attracted to the life drawing room where I determined to develop my skills as a figurative painter. I found myself to be an intuitive painter. I had little patience with the intellectual processes and conclusions which were involved with abstract and conceptual art. For me, to paint what I saw or felt or imagined around me should be a simple affair, painted from the gut.

“Above all, I try to speak with my own voice and see with my own eyes”

Graham Knuttel